The song I Want to Hold Your Hand represents a special moment in the history of the Beatles, and I am not referring to the fact that it was responsible for breaking the band in America. This was the first release by a rock and roll act to make use of EMI's four-track equipment at Abbey Road Studios, usually reserved for serious classical artists. After a year of recording on two-track tape, this was considered a high honor for the band that was now making a small fortune for the Parlophone label.

Of course, it was also the song that opened the floodgates in the USA, starting the British Invasion. Manager Brian Epstein had asked Lennon and McCartney to write a composition with the American audience in mind and, supposedly, they did so. I've been listening to it for most of my life and I have read much that has been written about it, but I'll be damned if I can hear anything specifically "American" about the song that separates it from their body of work up to that time. To me, it simply builds on the excitement of the previous single She Loves You and solidifies the sound that was uniquely their own. In fact, there was nothing else even remotely like it on American radio. Nothing.

The group had nearly completed the sessions for their second album With the Beatles when they turned their attention to their next single on October 17th, 1963. They had rehearsed the song in advance, so only a few adjustments were necessary during the seventeen takes that it took to achieve the master. A very young Geoff Emerick, who was serving as second engineer on this date, reports that John often flubbed the lyrics, thus resulting in so many takes. All four Beatles overdubbed handclaps onto the number before it was complete.

From its opening moments, I Want to Hold Your Hand is an infectious burst of energy (though less so than its predecessor She Loves You). Lennon and McCartney kept the lyrics as simple as can be, letting the drive of the performance, particularly their vocal duet, carry the song. It is John who makes the jump to falsetto each time on the first "hand," then Paul handles the high harmony for the second "your hand." The quiet bridge is sung in unison the first time through, then in one of their trademark harmonies the second time, each time building to a crescendo on "I can't hide" (or, as Bob Dylan heard it, "I get high").

Pirated copies of the song made their way to radio stations in various US cities, forcing Capitol Records to move the release date from January 13th, 1964 to December 26th, 1963. The American label also chose the song to open the album Meet the Beatles! which was released on January 20th. In the UK, it was the group's fifth single and subsequently appeared on the EP The Beatles' Million Sellers in 1965 as well as on the LP A Collection of Beatles Oldies in '66.

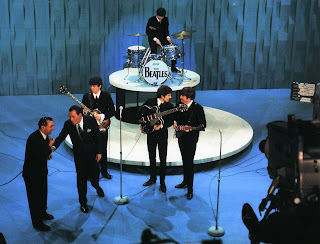

The song immediately made its way into their stage act. Its biggest impact naturally came from performances over three consecutive weeks on the Ed Sullivan Show in February of 1964. They continued to play the song throughout that landmark year and then never played it again.

Post-career releases include the Red Album in 1973, 20 Greatest Hits in 1982, Past Masters, Volume One in 1988 and 1 in 2000. Anthology 1 presents a sonic version from a live television performance for the Morecambe and Wise Show, and On Air - Live at the BBC Volume 2 features a recording for the radio program From Us to You. On this occasion, the boys overdubbed handclaps as they had on the original record, then applauded their own performance at the end.

More recently, the video collection 1+ has a black and white clip from the Granada Television program Late Scene Extra shot in Manchester and broadcast only days before the single's release in the UK. The band mimes to the record, with John and George oddly playing acoustic guitars.

Of course, it was also the song that opened the floodgates in the USA, starting the British Invasion. Manager Brian Epstein had asked Lennon and McCartney to write a composition with the American audience in mind and, supposedly, they did so. I've been listening to it for most of my life and I have read much that has been written about it, but I'll be damned if I can hear anything specifically "American" about the song that separates it from their body of work up to that time. To me, it simply builds on the excitement of the previous single She Loves You and solidifies the sound that was uniquely their own. In fact, there was nothing else even remotely like it on American radio. Nothing.

The group had nearly completed the sessions for their second album With the Beatles when they turned their attention to their next single on October 17th, 1963. They had rehearsed the song in advance, so only a few adjustments were necessary during the seventeen takes that it took to achieve the master. A very young Geoff Emerick, who was serving as second engineer on this date, reports that John often flubbed the lyrics, thus resulting in so many takes. All four Beatles overdubbed handclaps onto the number before it was complete.

From its opening moments, I Want to Hold Your Hand is an infectious burst of energy (though less so than its predecessor She Loves You). Lennon and McCartney kept the lyrics as simple as can be, letting the drive of the performance, particularly their vocal duet, carry the song. It is John who makes the jump to falsetto each time on the first "hand," then Paul handles the high harmony for the second "your hand." The quiet bridge is sung in unison the first time through, then in one of their trademark harmonies the second time, each time building to a crescendo on "I can't hide" (or, as Bob Dylan heard it, "I get high").

Pirated copies of the song made their way to radio stations in various US cities, forcing Capitol Records to move the release date from January 13th, 1964 to December 26th, 1963. The American label also chose the song to open the album Meet the Beatles! which was released on January 20th. In the UK, it was the group's fifth single and subsequently appeared on the EP The Beatles' Million Sellers in 1965 as well as on the LP A Collection of Beatles Oldies in '66.

The song immediately made its way into their stage act. Its biggest impact naturally came from performances over three consecutive weeks on the Ed Sullivan Show in February of 1964. They continued to play the song throughout that landmark year and then never played it again.

Post-career releases include the Red Album in 1973, 20 Greatest Hits in 1982, Past Masters, Volume One in 1988 and 1 in 2000. Anthology 1 presents a sonic version from a live television performance for the Morecambe and Wise Show, and On Air - Live at the BBC Volume 2 features a recording for the radio program From Us to You. On this occasion, the boys overdubbed handclaps as they had on the original record, then applauded their own performance at the end.

More recently, the video collection 1+ has a black and white clip from the Granada Television program Late Scene Extra shot in Manchester and broadcast only days before the single's release in the UK. The band mimes to the record, with John and George oddly playing acoustic guitars.